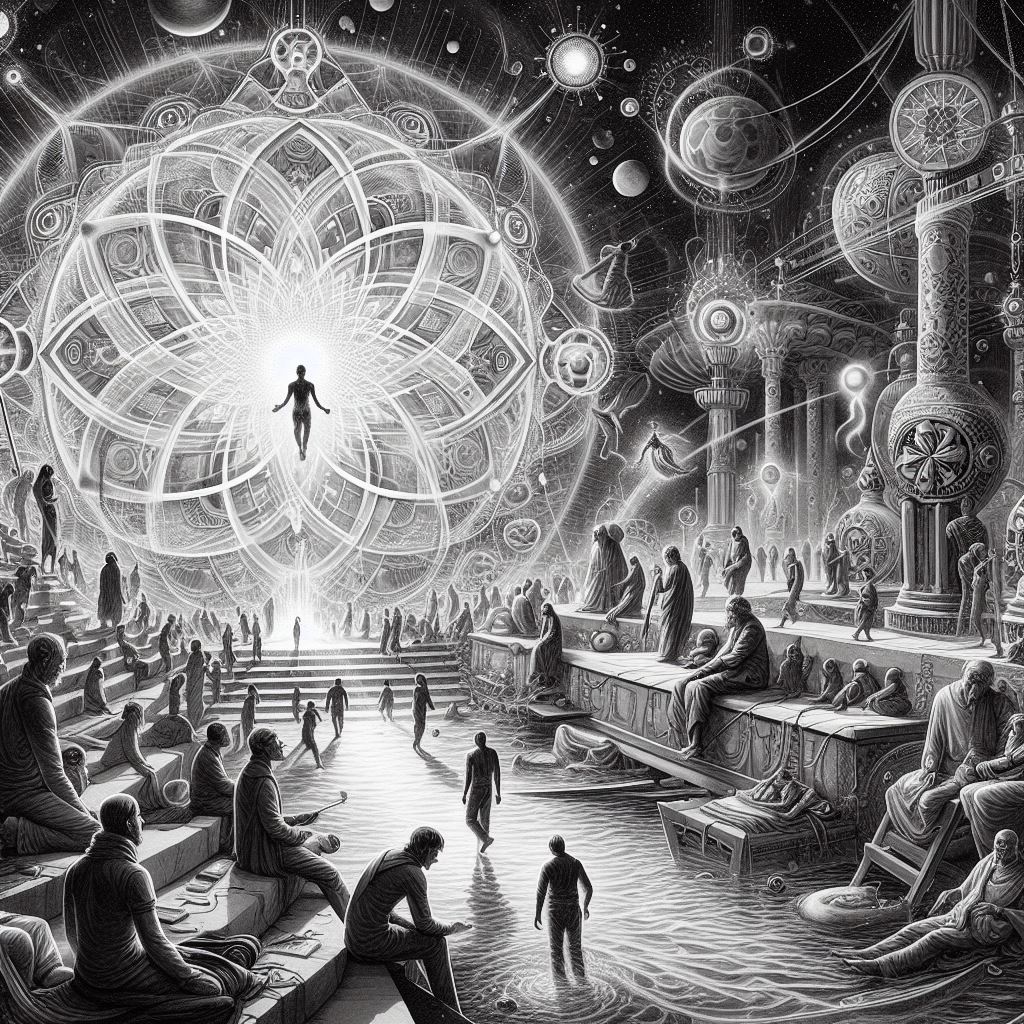

Among the oldest repositories of human knowledge, Vedic texts offer a sophisticated model of the mind that seems to fit very well with contemporary understanding. This paper is based on the Vedic model of the mind, focusing on its various components—Manas (mind), Buddhi (intellect), Ahaṃkāra (ego), and Chitta (consciousness). By comparing these with contemporary neuroscience and psychology, we aim to shed light on how Vedic wisdom brings a holistic approach to understanding the mind, possibly contributing to cognitive science, mental health, and consciousness studies.

Key words:

Vedic Psychology, Manas (Mind), Buddhi (Intellect), Consciousness Studies, Cognitive Neuroscience

Introduction

The Vedic tradition, with its roots in Nepal and India, provides profound insights into the nature of reality, existence, and the human mind. The Rishis (sages) of the Vedic era described the mind not merely as a psychological entity but as a complex system that integrates cognition, emotion, and consciousness. This article digs into the Vedic model of the mind, analyzing its components through the lens of modern science.

The Vedic Model of the Mind

The Vedic texts, primarily the Upaniṣadas, Bhagavad Gita, and Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras outline a quadruple model of the mind:

- Manas (Mind): The faculty of perception, emotion, and thought, Manas also Mana is responsible for processing sensory inputs and generating responses. It acts as the receiver of information, operating on a subconscious level, often influenced by habitual patterns and emotions.

In the Vedic model of the mind, Manas plays a pivotal role as the faculty of perception, emotion, and thought. It is responsible for processing sensory inputs and generating responses. In this section, we discuss the concept of Mana, supported by Vedic literature, examples, and modern scientific findings that make even with this ancient understanding.

- The Vedic Concept of Manas

Manas is described in the Vedic literature as the center of sensory perception and mental activity. It functions as the intermediary between the senses (Indriyas) and the intellect (Buddhi), receiving and processing sensory information before it is passed on for higher cognitive functions.

In the Mundaka Upaniṣada (3.1.9), the nature of Manas is described:

“मन एव मनुष्याणां कारणं बन्धमोक्षयोः। बन्धाय विषयासक्तं मुक्तं निर्विषयं स्मृतम्॥” “mana eva manuṣyāṇāṃ kāraṇaṃ bandhamokṣayoḥ, bandhāya viṣayāsaktaṃ muktaṃ nirviṣayaṃ smṛtam.”

“The mind alone is the cause of bondage and liberation for humans. Attached to sense objects, it leads to bondage; free from sense objects, it leads to liberation.”

This shloka emphasizes the dual role of Manas as both the source of worldly attachment and the key to spiritual liberation. It highlights how Manas, driven by habitual patterns and emotions, can either bind an individual to material desires or, when disciplined, lead to freedom from those desires.

- Functions of Manas

- Perception: Manas acts as the receiver of sensory inputs (sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell). For instance, when a person sees a flower, the eyes perceive the form and color, but it is Manas that integrates these sensory details into a coherent experience.

- Emotion: Manas is also the seat of emotions. When someone hears a pleasing melody, Manas processes the sound and generates an emotional response, such as joy or tranquility.

- Thought: Manas is involved in the formation of thoughts and mental imagery. It can reflect on past experiences or imagine future possibilities, often influenced by emotions and memories stored in Chitta.

In the Bhagavad Gita (6.34), Arjuna expresses the difficulty of controlling the mind:

चञ्चलं हि मन: कृष्ण प्रमाथि बलवद्दृढम् । तस्याहं निग्रहं मन्ये वायोरिव सुदुष्करम् ॥ cañcalaṃ hi mana: kṛṣṇa pramāthi balavaddṛḍham, tasyāhaṃ nigrahaṃ manye vāyoriva suduṣkaram ||

“The mind is restless, turbulent, powerful, and obstinate, O Krishna. It seems to me that it is more difficult to control than the wind.”

This verse illustrates Manas’ restless and unsteady nature, which can be dominated by fleeting thoughts and emotions, making it challenging to control.

1.3. Modern Scientific Correlates

In modern neuroscience, the functions attributed to Manas can be correlated with several brain regions responsible for processing sensory information, emotions, and thoughts.

- Perception and the Thalamus: The thalamus acts as a relay station in the brain, receiving sensory signals and directing them to the appropriate cortical areas. This process mirrors Manas’s role in processing sensory inputs before passing them to Buddhi for higher cognitive analysis.

- Emotion and the Limbic System: The limbic system, particularly the amygdala, is crucial for emotional processing. Manas’ role in generating emotional responses aligns with the functions of the limbic system, which interprets sensory inputs and triggers emotional reactions.

- Thought and the Default Mode Network (DMN): The DMN, active during rest and involved in self-referential thoughts, is similar to Manas in its capacity for mental imagery and spontaneous thought generation. The DMN’s activity reflects the restless and dynamic nature of Manas, as described in the Bhagavad Gita.

1.4. Habitual Patterns and Subconscious Influence

Manas (Mind) operates largely on a subconscious level, influenced by habitual patterns (Samskaras) and deep-seated tendencies (Vasanas). These subconscious imprints shape our perceptions, emotions, and thoughts, often without conscious awareness.

In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (1.2), the nature of these mental modifications is addressed:

“योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः॥” “yogaścittavṛttinirodhaḥ.”“Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind.”

Here, the “fluctuations of the mind” (chitta vrittis) are the habitual patterns that Manas repeatedly engages in, driven by past experiences and emotional responses. Controlling these fluctuations is essential for achieving mental clarity and balance.

Modern Findings:

- Neuroplasticity: The brain’s ability to form and reorganize synaptic connections, especially in response to learning or experience, aligns with the concept of Samskaras influencing Manas. Repeated thoughts and behaviors strengthen certain neural pathways, making them more likely to recur—akin to the Samskaras that drive habitual mental patterns.

- Subconscious Processing: Modern psychology recognizes that much of our mental processing occurs below the level of conscious awareness. This subconscious processing influences decisions, emotions, and perceptions, paralleling the Vedic understanding of Manas as being shaped by deep-seated tendencies.

1.5. Implications for Mental Discipline

The Vedic texts advocate for disciplining Manas through practices like meditation, mindfulness, and self-inquiry to transcend their habitual patterns and achieve a higher state of consciousness.

In Yoga Sutras (1.12), Patanjali advises:

“अभ्यासवैराग्याभ्यां तन्निरोधः॥” “abhyāsavairāgyābhyāṃ tannirodhaḥ.”“The fluctuations of the mind are controlled by practice and non-attachment.”

This suggests that regular practice (abhyāsa) and detachment from sensory objects (vairāgya) are key to controlling the restless nature of Manas.

Modern Practices:

- Mindfulness Meditation: Mindfulness practices in modern psychology help individuals observe their thoughts and emotions without attachment, reducing the habitual reactivity of Manas and promoting mental clarity.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT techniques focus on identifying and changing habitual thought patterns, aligning with the Vedic approach to managing the mind’s fluctuations through awareness and discipline.

The Vedic concept of Manas as the faculty of perception, emotion, and thought is deeply intertwined with modern scientific understandings of the brain’s functioning. By recognizing the subconscious influences and habitual patterns that shape our mental experiences, the Vedic model offers a holistic approach to cultivating mental discipline and achieving higher states of consciousness. Integrating these ancient insights with contemporary practices like mindfulness and cognitive therapy can enhance our understanding of the mind and improve mental well-being.

- Buddhi (Intellect): The discriminative faculty, Buddhi, is responsible for reasoning, judgment, and decision-making. It represents the higher mind, capable of introspection, analysis, and the pursuit of truth. Buddhi is the seat of wisdom and discernment, guiding actions in alignment with Dharma (universal law).

In the Vedic model of the mind, Buddhi represents the faculty of intellect, responsible for reasoning, judgment, and decision-making. As the higher mind, Buddhi enables introspection, analysis, and the pursuit of truth, serving as the seat of wisdom and discernment. It is essential for guiding actions in alignment with Dharma (universal law). Here we explore the concept of Buddhi, supported by the examples from Vedic texts, and modern scientific findings that highlight its significance.

2.1. The Vedic Concept of Buddhi

Buddhi is considered the most refined aspect of the mind, associated with clarity, discrimination, and wisdom. It is the faculty that allows individuals to distinguish between right and wrong, truth and illusion, and to make decisions based on ethical and moral considerations. In the Vedic tradition, Buddhi is regarded as essential for spiritual growth and aligning one’s actions with Dharma.

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna describes the nature of Buddhi:

“प्रवृत्तिं च निवृत्तिं च कार्याकल्ये भयाभये । बन्धं मोक्षं च या वेत्ति बुद्धिः सा पार्थ सात्त्विकी॥” “pravṛttiṃ ca nivṛttiṃ ca kāryākalye bhayābhaye, bandhaṃ mokṣaṃ ca yā vetti buddhiḥ sā pārtha sāttvikī.”“That intellect which understands the path of action and renunciation, what ought to be done and what ought not to be done, what is to be feared and what is not to be feared, what binds and what liberates, that intellect, O Arjuna, is in the mode of goodness (sattvic).”

This shloka emphasizes the role of Buddhi in discerning appropriate actions, recognizing what leads to bondage or liberation, and distinguishing between ethical and unethical choices. A sattvic (pure and balanced) Buddhi aligns with truth and righteousness, guiding the individual toward spiritual liberation.

2.2. Functions of Buddhi

- Reasoning and Judgment: Buddhi is the faculty that allows for logical analysis and critical thinking. It evaluates different possibilities and makes judgments based on reason and ethical principles. For example, in decision-making, Buddhi assesses the consequences of actions and chooses the one that aligns with Dharma.

- Introspection and Self-Inquiry: Buddhi facilitates introspection, enabling individuals to reflect on their thoughts, actions, and motivations. Through self-inquiry, one can recognize deeper truths about the self and the world.

- Pursuit of Truth: Buddhi is inherently oriented toward the pursuit of truth (Satya). It seeks to understand the underlying reality of existence, beyond mere appearances or illusions (Maya). In spiritual practices, Buddhi plays a crucial role in discerning the eternal from the transient.

In the Mahabharata, the character of Yudhishthira exemplifies a strong and sattvic Buddhi. Despite the many challenges and temptations he faces, Yudhishthira consistently makes decisions based on Dharma. His commitment to truth and righteousness, even in the face of personal loss, illustrates the guiding power of Buddhi.

2.3. Modern Scientific Correlates

In contemporary neuroscience, the functions attributed to Buddhi can be correlated with various brain regions involved in higher cognitive processes, ethical reasoning, and decision-making.

- Prefrontal Cortex: The prefrontal cortex is associated with executive functions such as planning, decision-making, and social behavior. It is crucial for reasoning, judgment, and impulse control, closely paralleling the role of Buddhi in making decisions based on ethical considerations and long-term consequences.

- Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): The ACC is involved in error detection, conflict monitoring, and decision-making. It helps in weighing the pros and cons of different actions, reflecting Buddhi’s function of discriminative reasoning.

- Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (vmPFC): The vmPFC is linked to the evaluation of morality and social decision-making. It helps in making choices that align with personal values and ethical standards, akin to Buddhi’s alignment with Dharma.

2.4. Buddhi and Dharma

Buddhi is deeply connected to Dharma, the moral and ethical law that governs the universe. In the Vedic tradition, Dharma is not merely a set of rules but a cosmic principle that upholds order, righteousness, and harmony. Buddhi, when pure and balanced, naturally aligns with Dharma, guiding individuals to act in ways that support the greater good.

In the Bhagavad Gita second chapter, Krishna reassures Arjuna of the importance of acting with Buddhi aligned with Dharma:

“नेहाभिक्रमनाशोऽस्ति प्रत्यवायो न विद्यते। स्वल्पमप्यस्य धर्मस्य त्रायते महतो भयात्॥” “nehābhikramanāśoʼsti pratyavāyo na vidyate, svalpamapyasya dharmasya trāyate mahato bhayāt.”“In this path, there is no loss of effort, nor is there any adverse result. Even a little practice of this Dharma protects one from great fear.”

This shloka suggests that even a small effort to align Buddhi with Dharma can lead to significant spiritual protection and growth. Buddhi, when used wisely, becomes a powerful tool for navigating life’s challenges while remaining true to universal principles.

In the Ramayana, Bhagawan Sri Rama consistently uses his Buddhi to adhere to Dharma, even when faced with personal difficulties. His decision to honor his father’s promise and go into exile, despite the hardships, exemplifies the application of Buddhi in upholding Dharma.

2.5. Modern Findings and Ethical Decision-Making

The study of ethical decision-making in psychology and neuroscience has revealed that the brain’s higher cognitive functions are essential in making decisions that align with moral values.

Moral Reasoning:

- Dual-Process Theory: Modern psychology suggests that moral reasoning involves both intuitive and rational processes. The rational process, which engages the prefrontal cortex, is reflective of Buddhi’s role in thoughtful, deliberate decision-making.

- Moral Development Theories: Theories such as Kohlberg’s stages of moral development describe the evolution of ethical reasoning from self-interest to universal ethical principles. Buddhi’s role aligns with the highest stages of moral development, where decisions are made based on universal truths rather than personal gain.

Neuroscience of Wisdom:

- Wisdom and the Brain: Studies on wisdom suggest that it involves a combination of cognitive and emotional regulation processes, primarily governed by the prefrontal cortex. Wisdom, as associated with Buddhi, requires the integration of knowledge with experience and the ability to make judgments that serve the greater good.

2.6. Cultivating Buddhi: Practices and Techniques

The Vedic tradition offers various practices to cultivate and refine Buddhi, enhancing its ability to guide individuals in alignment with Dharma.

Meditation and Mindfulness:

- Vipassana (Insight Meditation): This practice involves observing the mind and its processes with clarity and equanimity. It helps in sharpening Buddhi by allowing individuals to see things as they truly are, beyond biases and preconceived notions.

Study of Scriptures (Svadhyaya):

- Scriptural Study: Engaging with texts like the Upaniṣadas, Bhagavad Gita, and Yoga Sutras helps in refining Buddhi by exposing it to the highest truths and ethical principles. This practice encourages introspection and the application of wisdom in daily life.

Ethical Living (Yamas and Niyamas):

- Yamas and Niyamas: The ethical guidelines from Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, such as non-violence (Ahimsa), truthfulness (Satya), and contentment (Santosha), serve as practical applications of Buddhi in daily life. By adhering to these principles, Buddhi is strengthened and aligned with Dharma.

Buddhi, as described in the Vedic tradition, is the faculty of intellect that allows for reasoning, judgment, and the pursuit of truth. It is crucial for making decisions that align with Dharma and lead to spiritual growth. Modern scientific findings in neuroscience and psychology reveal parallels with the functions of Buddhi, highlighting its importance in ethical decision-making and wisdom. By cultivating Buddhi through practices like meditation, mindfulness, and ethical living, individuals can refine their intellect and align their actions with universal principles, leading to a life of righteousness and inner peace.

- Ahaṃkāra (Ego): Ahaṃkāra refers to the sense of individuality and identity, the “I-maker.” It creates the notion of self, differentiating the individual from the external world. While necessary for functioning in the physical world, Ahaṃkāra can lead to egoistic tendencies if not balanced by Buddhi.

In the Vedic model of the mind, Ahaṃkāra is the faculty responsible for the sense of individuality and identity—the “I-maker.” It creates the notion of self, distinguishing the individual from the external world. While Ahaṃkāra is essential for navigating and functioning in the physical world, it can lead to egoistic tendencies if not balanced by Buddhi (intellect). This section explores the concept of Ahaṃkāra, its role in the human psyche, and the potential challenges it presents, supported by Sanskrit shlokas, examples from Vedic texts, and insights from modern psychology.

3.1. The Vedic Concept of Ahaṃkāra

Ahaṃkāra is derived from two Sanskrit words: “Aham” meaning “I” and “Kara” meaning “maker” or “doer.” Thus, Ahaṃkāra translates to “I-maker,” referring to the ego’s role in forming the sense of personal identity. Ahaṃkāra is what gives rise to the experience of “I” and “mine,” creating a boundary between the self and the external world.

In the Vedic tradition, Ahaṃkāra is understood as both a necessary aspect of human consciousness and a potential source of delusion (Maya). It enables individuals to assert their existence, interact with the world, and fulfill their roles in society. However, when Ahaṃkāra becomes overly dominant, it can lead to egocentric behavior, attachment, and suffering.

In the Bhagavad Gita (3.27), Krishna speaks about the role of Ahaṃkāra:

“प्रकृतेः क्रियमाणानि गुणैः कर्माणि सर्वशः। अहङ्कारविमूढात्मा कर्ताहमिति मन्यते॥””prakṛteḥ kriyamāṇāni guṇaiḥ karmāṇi sarvaśaḥ, ahaṅkāravimūḍhātmā kartāhamiti manyate.”“All actions are performed by the modes of material nature, but a person deluded by the ego thinks, ‘I am the doer.'”

This shloka highlights how Ahaṃkāra can lead to the false belief that one is the sole doer of actions, ignoring the influence of Prakriti (nature) and the divine forces at play. This identification with the ego as the doer is a key source of attachment and suffering.

3.2. Functions of Ahaṃkāra

- Sense of Individuality: Ahaṃkāra gives rise to the perception of a distinct, individual self. It allows a person to recognize themselves as a separate entity with personal thoughts, desires, and experiences. For example, when someone says “I am hungry” or “I am successful,” it is Ahaṃkāra that asserts this personal identity.

- Differentiation from the External World: Ahaṃkāra helps distinguish between the self and others, between “me” and “not me.” This differentiation is crucial for personal identity and survival, as it allows individuals to interact with the world, form relationships, and pursue personal goals.

- Facilitating Social Roles: In the physical world, Ahaṃkāra enables individuals to fulfill their social roles and responsibilities. For instance, a teacher must identify with their role to effectively educate students, and a parent must recognize their role in caring for their child.

In the Mahabharata, the character of Duryodhana exemplifies the dangers of an unchecked Ahaṃkāra. His excessive pride and sense of entitlement, rooted in a strong Ahaṃkāra, lead him to make decisions that ultimately result in his downfall. Duryodhana’s refusal to see beyond his ego-driven desires causes immense suffering for himself and others.

3.3. Ahaṃkāra and Its Potential Pitfalls

While Ahaṃkāra is necessary for functioning in the world, it can become problematic if it is overly dominant or unbalanced by Buddhi:

- Egoistic Tendencies: When Ahaṃkāra becomes inflated, it leads to egoism—an exaggerated sense of self-importance. This can manifest as arrogance, pride, and a desire for power and control. Individuals with an inflated Ahaṃkāra may prioritize their own needs and desires over the well-being of others.

- Attachment and Suffering: Ahaṃkāra can create an attachment to personal achievements, possessions, and relationships. This attachment often leads to suffering when these external sources of identity are threatened or lost. For example, a person who identifies strongly with their professional success may experience deep distress if they lose their job.

- Illusion of Separateness: Ahaṃkāra reinforces the illusion of separateness from others and the divine. This can lead to feelings of isolation, competition, and conflict, as the ego perceives others as threats to its identity or resources.

In the Isha Upaniṣada (Mantra 1), the interconnectedness of all beings is emphasized, countering the separateness fostered by Ahaṃkāra:

“ईशावास्यमिदं सर्वं यत्किञ्च जगत्यां जगत्। तेन त्यक्तेन भुञ्जीथा मा गृधः कस्यस्विद्धनम्॥” īśāvāsyamidaṃ sarvaṃ yatkiñca jagatyāṃ jagat, tena tyaktena bhuñjīthā mā gṛdhaḥ kasyasviddhanam.”“The Lord pervades everything in this universe. Therefore, one should enjoy life with a sense of detachment and not covet others’ wealth.”

This shloka reminds us that everything is interconnected and belongs to the divine, urging detachment from egoistic desires and the illusion of separateness created by Ahaṃkāra.

3.4. Balancing Ahaṃkāra with Buddhi

To prevent Ahaṃkāra from leading to negative consequences, it must be balanced by Buddhi, the faculty of intellect and discernment. Buddhi helps temper the ego’s tendencies by promoting self-awareness, ethical reasoning, and alignment with Dharma.

- Self-Reflection: Regular self-reflection helps individuals recognize when Ahaṃkāra is driving their thoughts and actions. By examining their motives and the impact of their actions on others, individuals can bring their egos into check.

- Cultivating Humility: Humility is a powerful antidote to an inflated Ahaṃkāra. Recognizing the limitations of one’s knowledge and abilities, and appreciating the contributions of others, helps keep the ego in balance.

- Service and Compassion: Engaging in selfless service (Seva) and cultivating compassion for others can reduce the dominance of Ahaṃkāra. These practices shift the focus from the self to the well-being of others, aligning actions with Dharma.

Example from the Bhagavad Gita:

In the Bhagavad Gita (2.47), Krishna advises Arjuna on the importance of selfless action, free from egoistic attachment:

“कर्मण्येवाधिकारस्ते मा फलेषु कदाचन। मा कर्मफलहेतुर्भूर्मा ते सङ्गोऽस्त्वकर्मणि॥” “karmaṇyevādhikāraste mā phaleṣu kadācana, mā karmaphalaheturbhūrmā te saṅgoʼstvakarmaṇi.”“You have the right to perform your duty, but not to the fruits of your actions. Let not the fruits of action be your motive, nor let your attachment be to inaction.”

This verse emphasizes acting without attachment to outcomes, which is a way to transcend the ego-driven desire for personal gain.

3.5. Modern Psychological Insights

Modern psychology provides insights into the concept of Ahaṃkāra, particularly through the study of the ego and its role in personality development.

- Ego in Psychology: The ego, as described by Sigmund Freud, is the component of the psyche that mediates between the id (instinctual desires), the superego (moral conscience), and reality. Like Ahaṃkāra, the ego is responsible for the sense of self and personal identity. However, an overactive ego can lead to issues such as narcissism, where the sense of self becomes overly inflated.

- Self-Concept and Identity: Psychological research on self-concept examines how individuals perceive themselves and construct their identities. An unbalanced self-concept, overly focused on external achievements and recognition, can lead to emotional distress and relationship problems—paralleling the challenges of an unchecked Ahaṃkāra.

- Mindfulness and Ego Reduction: Mindfulness practices, which encourage present-moment awareness and non-attachment, have been shown to reduce egoic tendencies and increase psychological well-being. This aligns with the Vedic approach of balancing Ahaṃkāra with self-awareness and detachment.

3.6. Transcending Ahaṃkāra in Spiritual Practice

In the Vedic tradition, the ultimate goal is not to eliminate Ahaṃkāra but to transcend it, recognizing the true Self (Atman) beyond the ego.

- Self-Realization (Atma Jnana): Self-realization involves understanding that the true Self is not the ego, but the Atman—pure consciousness, which is eternal and beyond individual identity. This realization dissolves the illusion of separateness created by Ahaṃkāra.

- Bhakti Yoga (Devotion): Bhakti Yoga emphasizes surrender to the divine and the dissolution of the ego in the love of God. By focusing on a higher power, practitioners reduce their identification with the ego and cultivate humility and devotion.

- Jnana Yoga (Path of Knowledge): Jnana Yoga involves the study of scriptures and contemplation on the nature of the Self. Through this process, practitioners discern the difference between the transient ego (Ahaṃkāra) and the eternal Self (Atman).

In the Katha Upaniṣada (2.1.15), the ultimate realization of the Self is described:

“यदा सर्वे प्रमुच्यन्ते कामा येऽस्य हृदि श्रिताः। अथ मर्त्योऽमृतो भवत्यत्र ब्रह्म समश्नुते॥” “yadā sarve pramucyante kāmā yeʼsya hṛdi śritāḥ, atha martyoʼmṛto bhavatyatra brahma samaśnaute.” “When all the desires that dwell in the heart fall away, then the mortal becomes immortal and attains

- Chitta (Consciousness): Chitta is the storehouse of memories, impressions (Samskaras), and deep-seated tendencies (Vasanas). It is the substratum of the mind, encompassing all mental activities and being closely linked to the concept of the subconscious.

In the Vedic model of the mind, Chitta represents a fundamental aspect of consciousness, acting as the storehouse of memories, impressions (Samskaras), and deep-seated tendencies (Vasanas). As the substratum of the mind, Chitta encompasses all mental activities, playing a crucial role in shaping thoughts, behaviors, and experiences. It is closely linked to the concept of the subconscious, housing latent impressions that influence the conscious mind. This section explores the concept of Chitta, supported by Sanskrit shlokas, examples from Vedic texts, and insights from modern psychology and neuroscience.

4.1. The Vedic Concept of Chitta

Chitta is often referred to as the “mind-stuff” or the “field of consciousness” in the Vedic tradition. It serves as the repository for all mental impressions, thoughts, memories, and experiences, both conscious and unconscious. Chitta is not just a passive storage but actively influences the mind’s activities, shaping how individuals perceive the world, react to situations, and form their identity.

In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (1.2), the nature of Chitta is described as:

“योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः॥” “yogaścittavṛttinirodhaḥ.” “Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind (Chitta).”

This sutra highlights that the practice of Yoga aims to quiet the fluctuations or disturbances in Chitta, allowing the practitioner to experience a state of pure consciousness and inner stillness. Chitta is thus the field where all mental activities occur, and mastering it is key to achieving mental clarity and spiritual growth.

4.2. Functions of Chitta

- Storehouse of Samskaras (Impressions): Chitta holds the Samskaras, which are the subtle impressions left by every experience, thought, and action. These impressions can be positive, negative, or neutral, and they shape future behaviors and tendencies. For instance, a person who repeatedly experiences fear in certain situations may develop a deep-seated tendency (Vasana) towards anxiety in similar contexts.

- Reservoir of Vasanas (Tendencies): Vasanas are the latent tendencies or habitual patterns that arise from Samskaras stored in Chitta. These tendencies influence behavior and decision-making, often operating below the level of conscious awareness. For example, a person with a strong Vasana for compassion may instinctively help others without deliberate thought.

- Subconscious Mind: Chitta is closely associated with the subconscious, containing all the mental content that is not immediately accessible to the conscious mind. It influences thoughts, emotions, and actions in subtle ways, often guiding behavior without the individual’s conscious realization.

In the Ramayana, the character of Bhagawan Sri Rama demonstrates the impact of positive Samskaras and Vasanas. Despite facing numerous challenges, Rama’s deep-seated tendencies towards righteousness, duty, and compassion consistently guide his actions. His Chitta is pure, shaped by virtuous Samskaras that lead him to act in accordance with Dharma.

4.3. The Dynamics of Samskaras and Vasanas

Samskaras and Vasanas are intricately connected within Chitta, forming the basis for the patterns of thought and behavior that manifest in an individual’s life.

- Formation of Samskaras: Every experience, thought, and action leaves an imprint on Chitta, creating Samskaras. These impressions accumulate over time, reinforcing certain patterns and tendencies. For example, if someone consistently practices kindness, the Samskaras of kindness become stronger, making compassionate behavior more natural.

- Manifestation of Vasanas: Over time, the accumulated Samskaras give rise to Vasanas, which are the habitual tendencies that influence behavior. Vasanas can be seen as the seeds that eventually manifest as thoughts, emotions, and actions. If a person has strong Vasanas related to anger, they may frequently experience irritation or rage in triggering situations.

In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (4.9), the continuity of Samskaras and Vasanas across lifetimes is described:

“जाति देश काल व्यवहितानामप्यनन्तर्यं स्मृति संस्कारयोरेक रूपत्वात्॥” “jāti deśa kāla vyavahitānāmapyanantaryaṃ smṛti saṃskārayoreka rūpatvāt.”“There is a continuity in the nature of memory and Samskaras, even if separated by birth, time, and place.”

This sutra suggests that Samskaras and Vasanas persist beyond a single lifetime, influencing an individual’s consciousness across different incarnations. This continuity explains why certain tendencies and impressions seem innate or difficult to change.

4.4. Chitta and the Subconscious Mind

The concept of Chitta closely aligns with the idea of the subconscious mind in modern psychology. Just as Chitta holds Samskaras and Vasanas, the subconscious mind stores memories, instincts, and repressed emotions that shape behavior and perception.

- Influence on Conscious Behavior: Although Chitta (or the subconscious) is not directly accessible to the conscious mind, it significantly influences conscious thoughts and actions. For example, unresolved emotional issues stored in Chitta can manifest as irrational fears or compulsive behaviors in daily life.

- Dreams and Chitta: In both Vedic thought and modern psychology, dreams are often seen as a window into the subconscious. The content of dreams can reveal the Samskaras and Vasanas stored in Chitta, offering insights into unresolved issues or deep-seated desires.

In the Mahabharata, the character of Arjuna experiences a crisis of identity and purpose on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, reflecting the influence of deep-seated Samskaras in his Chitta. His initial hesitation to fight against his relatives and teachers can be seen as a manifestation of conflicting Vasanas, which are eventually resolved through the guidance of Krishna, who helps him align his Chitta with Dharma.

4.5. Modern Psychological and Neuroscientific Insights

Modern psychology and neuroscience provide valuable insights into the functions of Chitta, particularly in understanding the role of the subconscious mind, memory, and habitual behavior.

- Subconscious Mind in Psychology: The subconscious mind, as described by psychologists like Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, parallels the concept of Chitta. It is the repository for all thoughts, memories, and impulses that are not currently in conscious awareness. These subconscious elements influence behavior, often in ways that are not immediately obvious.

- Implicit Memory: Neuroscience identifies the concept of implicit memory, which refers to memories that are not consciously recalled but influence behavior. These are similar to Samskaras in Chitta, where past experiences shape future actions without conscious awareness.

- Neural Pathways and Habits: Modern neuroscience also explores how repeated behaviors and thoughts form neural pathways in the brain, which become the basis for habitual behavior. This is analogous to the formation of Vasanas in Chitta, where repeated actions create strong tendencies that guide future behavior.

Neuroplasticity and Changing Samskaras:

- Neuroplasticity: The brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections is known as neuroplasticity. This concept aligns with the Vedic idea that Samskaras and Vasanas can be transformed through conscious effort and practice. By engaging in positive thoughts and actions, one can rewire the brain and cultivate beneficial Samskaras.

4.6. Transforming Chitta Through Spiritual Practice

In the Vedic tradition, Chitta is not static; it can be purified and transformed through spiritual practices such as meditation, self-inquiry, and ethical living.

- Meditation (Dhyana): Meditation is a key practice for purifying Chitta. By focusing the mind and calming its fluctuations, one can access deeper layers of consciousness and begin to dissolve negative Samskaras. Over time, regular meditation can lead to the formation of positive Samskaras, promoting peace, clarity, and spiritual growth.

- Self-Inquiry (Svadhyaya): Self-inquiry involves introspection and the study of sacred texts to understand the nature of the self. This practice helps in identifying and transforming Vasanas that are rooted in ignorance or attachment, leading to greater self-awareness and liberation from the cycles of Samskaras.

- Ethical Living (Yamas and Niyamas): Adhering to ethical principles, such as non-violence (Ahimsa), truthfulness (Satya), and contentment (Santosha), helps in cultivating positive Samskaras and reducing the influence of negative tendencies in Chitta. These principles are outlined in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras as foundational practices for mental purification.

In the Katha Upaniṣada (1.3.13), the path to self-realization and the purification of Chitta is described:

“नायमात्मा प्रवचननेन लभ्यो न मेधया न बहुना श्रुतेन। यमेवैष वृणुते तेन लभ्यः तस्यैष आत्मा विवृणुते तनूं स्वाम्॥” “nāyamātmā pravacananena labhyo na medhayā na bahunā śrutena, yamevaiṣa vṛṇute tena labhyaḥ tasyaiṣa ātmā vivṛṇute tanūṃ svām.” “The Self is not attained by discourse, nor by intellect, nor by much learning. It is attained by him who longs for it, and to him the Self reveals its true nature.”

This verse emphasizes that the true nature of the Self, which lies beyond the fluctuations of Chitta, can only be realized through sincere longing and the purification of the mind.

Chitta, as described in the Vedic tradition, is the substratum of the mind, encompassing all memories, impressions (Samskaras), and tendencies (Vasanas). It plays a crucial

Modern Scientific Correlates to the Vedic Model of Mind

The Vedic model of the mind offers a profound understanding of human consciousness, emotions, and behavior, which is increasingly echoed in modern neuroscience and psychology. This section explores the correlations between the Vedic components of the mind—Manas, Buddhi, Ahaṃkāra, and Chitta—and their modern scientific counterparts in the brain, supported by relevant scientific findings.

- Manas and the Limbic System

Manas in the Vedic tradition is responsible for perception, emotion, and the processing of sensory inputs. It acts on a subconscious level, influenced by habitual patterns and emotions.

The Limbic System in the brain, comprising structures like the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus, is involved in emotions, motivation, and certain memory functions.

Correlation:

The Limbic System closely aligns with Manas:

- Emotional Processing: Manas governs emotional responses, just as the limbic system, particularly the amygdala, is central to generating emotions like fear and pleasure.

- Sensory Input Processing: Manas processes sensory inputs into perceptions, while the limbic system integrates sensory information with emotional context, influencing perceptions and reactions.

- Memory Formation: The hippocampus, a key component of the limbic system, is essential for forming memories tied to sensory experiences, reflecting Manas’s role in storing sensory impressions.

Scientific Support:

Studies in neuroscience have shown that the amygdala plays a critical role in emotional memory and processing, which is essential for survival and learning. Research also indicates that the hippocampus is vital for the formation and retrieval of declarative memories, particularly those with an emotional component . This supports the Vedic understanding of Manas as integral to emotional and sensory processing.

- Buddhi and the Prefrontal Cortex

Buddhi is the discriminative faculty responsible for reasoning, judgment, and decision-making, reflecting the higher cognitive functions.

The Prefrontal Cortex is the part of the brain involved in complex cognitive behavior, including decision-making, planning, and ethical reasoning.

Correlation:

The Prefrontal Cortex mirrors the role of Buddhi:

- Decision-Making: Buddhi is responsible for making reasoned decisions, akin to how the prefrontal cortex enables logical analysis and ethical decision-making.

- Moral Reasoning: Buddhi guides actions in alignment with Dharma, while the prefrontal cortex is involved in moral reasoning and social behavior.

- Self-Control and Planning: Buddhi aids in introspection and impulse control, roles also managed by the prefrontal cortex, which is essential for planning and setting long-term goals.

Scientific Support:

Neuroscientific research has shown that the prefrontal cortex is crucial for tasks requiring planning, moral reasoning, and decision-making. Damage to this area can impair judgment and self-control, highlighting its role in higher-order cognitive functions . This aligns with Buddhi’s role as the guiding force for rational and ethical actions.

- Ahaṃkāra and the Default Mode Network (DMN)

Ahaṃkāra refers to the sense of individuality and identity, forming the notion of self and differentiating the individual from the external world.

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is a network of brain regions active during rest and self-referential thoughts, such as daydreaming and reflecting on one’s identity.

Correlation:

The Default Mode Network correlates with Ahaṃkāra:

- Self-Referential Thought: Ahaṃkāra creates the self-identity, similar to how the DMN is engaged in self-referential thinking, including reflections on self-concept and ego.

- Sense of Identity: Ahaṃkāra fosters the sense of individual identity, just as the DMN is involved in constructing and maintaining the self-concept.

- Internal Focus: Ahaṃkāra drives self-focused thoughts, paralleling the DMN’s activity during internal, ego-related reflections.

Scientific Support:

Research on the Default Mode Network shows that it is particularly active during periods of introspection and self-referential activities, such as thinking about oneself or recalling personal memories . This supports the Vedic view of Ahaṃkāra as the aspect of mind that creates and maintains a sense of self.

- Chitta and the Unconscious Mind

Chitta is the repository of memories, impressions (Samskaras), and deep-seated tendencies (Vasanas), functioning as the substratum of the mind and linked to the subconscious.

The Unconscious Mind in modern psychology stores all memories, experiences, and learned behaviors not in immediate conscious awareness, influencing behavior through deep-seated impressions.

Correlation:

Chitta resonates with the Unconscious Mind:

- Storage of Impressions: Chitta holds Samskaras, or accumulated impressions from past experiences, similar to how the unconscious mind stores memories and experiences that shape behavior unconsciously.

- Influence on Behavior: Chitta influences thoughts and actions through Vasanas, much like the unconscious mind shapes behavior through repressed memories and learned behaviors.

- Subconscious Processing: Chitta operates below conscious awareness, akin to the subconscious processing in the unconscious mind, influencing decision-making and behavior.

Scientific Support:

Psychological studies indicate that the unconscious mind plays a significant role in influencing behavior, often through implicit memories and learned behaviors that operate without conscious awareness . This understanding supports the Vedic concept of Chitta as the repository of deep-seated mental impressions.

Hence, The parallels between the Vedic model of the mind and modern scientific findings underscore the profound wisdom embedded in ancient spiritual traditions. Neuroscience and psychology increasingly validate the insights provided by Vedic teachings, with Manas aligning with the Limbic System, Buddhi with the Prefrontal Cortex, Ahaṃkāra with the Default Mode Network, and Chitta with the Unconscious Mind. These correlations reveal a shared understanding of the mind’s structure and function, bridging the gap between ancient wisdom and contemporary science.

Integration and Implications of the Vedic Model of the Mind

The Vedic model of the mind, rooted in ancient Indian philosophy, offers a holistic and integrative framework that encompasses the emotional, cognitive, and conscious dimensions of human experience. By understanding the interplay between different mental faculties—Manas (Mind), Buddhi (Intellect), Ahaṃkāra (Ego), and Chitta (Consciousness)—this model provides profound insights into mental processes and well-being. The implications of this model are significant across various fields, including cognitive science, mental health, and consciousness studies.

- Cognitive Science: Enhancing Understanding of Mental Processes

The Vedic model’s detailed analysis of the mind provides a sophisticated conceptualization of mental processes that can significantly contribute to cognitive science.

- Deep Integration of Cognitive Functions: In modern cognitive science, the study of mental functions such as perception, memory, decision-making, and self-identity is often fragmented. The Vedic model, however, offers an integrated view where these functions are interdependent and collectively contribute to the overall functioning of the mind. For instance, Manas (the sensory mind) and Buddhi (the intellect) are seen as complementary forces where perception and reasoning are not isolated but are dynamically interconnected. This integrated approach can inspire new research methodologies that consider the mind’s operations as a holistic system rather than as discrete processes.

- Nature of Consciousness: Cognitive science struggles with the “hard problem of consciousness”—explaining how subjective experiences arise from neural processes. The Vedic concept of Chitta as the repository of consciousness and its link to both the conscious and subconscious mind offers a framework that bridges this gap by considering consciousness not just as a byproduct of brain activity but as an inherent aspect of existence. This perspective can open new avenues in consciousness studies, encouraging explorations that transcend purely materialistic interpretations of mind and consciousness.

- Cultural and Philosophical Integration: Incorporating the Vedic model into cognitive science can also enrich the field by integrating diverse cultural and philosophical perspectives. This can lead to a more inclusive understanding of the mind that respects and incorporates non-Western paradigms, fostering a global and culturally aware approach to the study of cognition.

- Mental Health: Promoting Balance and Well-Being

The Vedic model emphasizes the importance of balance among the different aspects of the mind for maintaining mental health and well-being. This concept can be highly valuable in modern therapeutic practices.

- Addressing Imbalances: Many psychological disorders can be viewed as imbalances in the mind’s components. For example, an overactive Ahaṃkāra (ego) may lead to narcissistic tendencies or anxiety, while a weakened Buddhi (intellect) might result in poor decision-making and a lack of self-control. The Vedic approach suggests that by bringing these faculties into balance—strengthening Buddhi to guide Ahaṃkāra, and calming Manas to reduce emotional turbulence—mental health can be significantly improved. This can inform therapies that aim not just to treat symptoms but to restore harmony within the mind’s structure.

- Holistic Therapeutic Practices: The Vedic emphasis on holistic well-being can inspire therapeutic practices that incorporate mindfulness, meditation, and ethical living as essential components of mental health. For instance, practices that calm Manas through sensory withdrawal and meditation (as found in Pratyahara in yoga) can help in reducing anxiety and stress, while enhancing Buddhi through reflective practices like Svadhyaya (self-study) can improve cognitive control and decision-making.

- Preventive Mental Health: The Vedic model also emphasizes preventive care by promoting a balanced life where all aspects of the mind are nurtured and maintained in harmony. This preventive approach can reduce the risk of developing psychological disorders, offering a proactive rather than reactive approach to mental health care.

- Consciousness Studies: Expanding the Exploration of Higher States

The Vedic exploration of consciousness, particularly through Chitta, provides a unique perspective that can contribute significantly to contemporary debates on the nature and origin of consciousness.

- Higher States of Consciousness: The Vedic tradition speaks of various levels of consciousness, including waking, dreaming, deep sleep, and higher states such as Turiya (the fourth state, often equated with pure consciousness). These states are not just theoretical but are accessible through disciplined practice and meditation, suggesting that consciousness is a continuum rather than a fixed state. This idea challenges the conventional understanding of consciousness as a static phenomenon and encourages the study of consciousness as a dynamic, evolving process.

- Subconscious and Unconscious Mind: Chitta is described as the repository of all past experiences and impressions (Samskaras), which influence current thoughts and behaviors. This understanding aligns with modern concepts of the unconscious but extends further by offering methods to purify and access these deeper layers of the mind through practices like Yoga and meditation. This perspective can enhance current models of the unconscious by incorporating techniques for consciously engaging with and transforming unconscious content.

- Spiritual Dimensions of Consciousness: The Vedic model also integrates the spiritual dimensions of consciousness, viewing it as not merely a product of brain activity but as a fundamental aspect of the cosmos. This aligns with certain contemporary theories in consciousness studies that propose consciousness as a primary aspect of the universe (e.g., panpsychism). The Vedic model, therefore, offers a robust framework for exploring these ideas in greater depth.

The Vedic model of the mind provides a rich, integrative framework that has profound implications for modern science and mental health. Its holistic approach emphasizes the interdependence of cognitive, emotional, and spiritual aspects of the mind, offering valuable insights for enhancing cognitive science, promoting mental well-being, and deepening the understanding of consciousness. By integrating these ancient concepts into modern contexts, we can develop more comprehensive and effective approaches to studying and nurturing the human mind, fostering greater mental harmony and well-being in both individual and collective spheres.

Conclusion

The Vedic mind model, with its fine division of mental faculties, brings timeless wisdom that underlies and helps in the deeper understanding and enrichment of modern scientific discoveries. Through this integration, one is likely to come up with a better way of understanding the complexity of the mind in further studies of cognition science, psychology, and consciousness. This synthesis will enhance the scientific perspective but also provide wholeness of approach to mental well-being, promoting balance and harmony in the mind. In this way, Vedic insights can contribute toward theoretically based knowledge with practical applications, which seem very promising for establishing a more integrative approach to study and care toward the human mind.

Reference:

-

- Bhagavad Gita As It Is: translated by Swami Prabhupada, The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1986.

- Mundaka Upaniṣad : The Upanishads, translated by Eknath Easwaran, Nilgiri Press, 2007.

- Yoga Sutras : The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, translated by Swami Satchidananda, Integral Yoga Publications, 2012.

- Yoga Sutras: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, translated by Edwin F. Bryant, North Point Press, 2009.

- Brahmacari, Dr Srivas Krishna Das. “Navigating the Shadows of Society Modern Woes: Insights and Solutions.” Lumbini Buddha printers, Koteshwor, JF Inc., (2018).

- Mahabharata, translated by C. Rajagopalachari, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 2002.

- Mahabharat, Gita press Gorakhapur.

- The Ramayana of Valmiki, translated by Hari Prasad Shastri, Shanti Sadan, 1952.

Views: 1017

Origin of Science

The Psychospiritual Roots of Crime

Unveiling 54 Vedic Scientists

The Existence of the Soul: Exploring Neuroscience, Quantum Physics and Vedic Philosophy

Temporal Relativity in Vedic Literature: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Time Dilation Narratives

Acharya Kaṇāda: The Ancient Sage Who Discovered the Atom

Evidence of Vedic Sanātana Hinduism as a Global Dharma

Perception of Quantum Gravity and Field Theory in the Vedas

String Theory as Mentioned in Veda

Sanskrit’s Role in Advancing AI: A Comprehensive Study

Vedic Contributions to Geometry: Unveiling the Origins of Mathematics

Matter and Consciousness in Achintya Bhedābheda: Bridging with Quantum Physics

A Comprehensive Study of Aeroplanes and Aviation in Vedic Literature